Oatmeal, Harry and the Westie

Harry loved oatmeal cookies and early on began to call his wife his sweet little Oatmeal Cookie, fondly, like Sugar or Honey. He shortened the pet name, not to Cookie as some men might have, but to Oatmeal, or sometimes just Oats. Their friends picked it up and so Oatmeal became her nickname, appropriate for someone with her sweet, bland nature, her light brown hair and her habit of dressing in browns and tans. At the local town library where she worked she kept her boringly average real first name, which soon ceased to feel like hers at all.

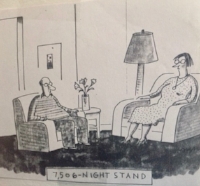

Oatmeal and Harry decided to separate one day while leafing through The New Yorker, as they did every week, looking at the cartoons. They came across one of a dowdy couple seated on a couch looking expressionlessly forward. The caption said: “The 7,506 night stand.” After laughing themselves silly, they looked at each other and simultaneously said a word they had fondly shared in other contexts, the word that John Updike used to end the multi-volume Rabbit Angstrom series. That word: enough.

Oatmeal and Harry sold the house they had lived in for many years for an absurd profit having timed the real estate cycles fortuitously. That and a small family inheritance and half the money she and Harry had saved and invested wisely let her quit her job at the library even though she was a few years short of normal retirement. Harry took the cats (she had never been a cat person).

Harry had a heart attack soon after their divorce, which they did simply with forms from a Nolo Press legal self-help book, splitting everything half and half. Experiencing a classic near-death, he woke up treasuring life in a way that led to adventures he shared by emailing Oatmeal, who cheered his bungee jumping, his travels to places that sounded exotic to her, even his graphically recounted romances.

Oatmeal, with no heart attack, no near-death experience and no (from what she patched together of Harry’s inspiration) mid-life crisis, bought and moved into a small Craftsman-style house where she vegetated quite happily. She called this a time of composting, though she had no ideas about what flowers or vegetables might grow out of the fertile soil of her open-ended respite.

Oatmeal bought the house from a woman named Jane and since the closing happened quickly, Oatmeal agreed that Jane could stay in the extra back bedroom while looking for a new place to live, an unusual arrangement that suited them both. Jane was rarely there and since Oatmeal was becoming more reclusive by the day, having someone who showed up from time to time reassured her rather than, as she had expected, felt intrusive.

Jane was under thirty and opposite in so many ways from Oatmeal. Short Oatmeal had gained around the middle; tall Jane was athletic. Oatmeal’s eyes were pale blue; Jane’s were intense blue: at times her eyes seemed to emit a laser-like beam. At home Oatmeal wore bluejeans and work shirts; Jane sometimes wore a soft silk blouse, gathered at the neck with a drawstring, and a matching long skirt of a dark sea-blue with flecks of intense indigo and a thin red ribbon threading through three layers of the skirt. Oatmeal obsessed; Jane did not. Jane danced; Oatmeal protected knees wrecked from years of running with Harry when they were young, never marathons, but serious 10K races. Harry thought about mathematics when he ran; only while running had Oatmeal felt free of worried thoughts.

When Jane was in town, they spent time together drinking tea. Jane sat in a comfortable rocking chair in the corner, usually knitting, while Oatmeal nestled into her window seat, covered by a bright blue chenille throw. Oatmeal would ramble on about whatever was on her mind while Jane listened, usually saying nothing until Oatmeal came to a stopping point in whatever narrative she was spinning to say only, "Jane, what should I do?" Jane would respond with a terse one-liner that Oatmeal realized was always the right thing, uncannily so, though often just the opposite of what she hoped to hear.

Harry came over for dinner every Tuesday night. The first time was to celebrate their divorce being final. Oatmeal could not remember who suggested a replay the following Tuesday but now months later, Harry assumed that at 7:00 every Tuesday he would ring the doorbell, hand Oatmeal a bouquet of flowers and settle in to chat and eat in her new house, decorated simply in vibrant Southwestern colors: rust with accents of teal and dark red. Oatmeal liked Jane’s use of intense color, so different from the slightly elegant but monotone house she had shared with Harry. Harry took the furniture since his new apartment was unfurnished and he had no desire to shop; Jane left hers for Oatmeal. It was all very casual and friendly.

Oatmeal noticed -- and if Harry did, he didn’t say -- a certain opposition in their post-marital development. For every pound Harry lost, Oatmeal seemed to gain one. Oatmeal’s face showed signs of aging, delicate lines, circles under her eyes, while Harry seemed younger (did he have a face lift, she wondered?) She cut her hair a bit shorter and stopped coloring it so that it now was ash blond tending to gray, while Harry let his grow a bit (he was lucky not to be balding). But mostly Harry was experiencing a sense of adventure, a catching up on what he had missed having married right out of graduate school, while she seemed quite content to stay quietly at home. And for whatever reason he needed to confide in her about his new joie de vivre, which she suspected was partly at least the work of his new health guru, a chiropractor who peddled supplements. After extensive blood tests, the chiropractor suggested Harry boost up his lagging hormones with testosterone and DHEA, the latter against the advice of their family doctor. So far Harry was thriving on daily plastic baggies full of pills, including vitamins and fish oil, resveratrol and various esoteric pills supposed to maintain his vision, his heart, his memory. Oatmeal relied on an estrogen patch and a drug store multi, which she often forgot, to ward off the inevitabilities of aging.

Harry had not met Jane, but he liked the idea of her renting a room. Renting, that is: why was Oatmeal not charging rent? Oatmeal told Harry Jane was her friend, she had sold the house at a reduced rate, she had left her furniture, she was hardly ever there. She didn’t mention that Jane’s terse one-liner tidbits of advice were worth many times the feedback she got from her worthless therapist, or rather ex-therapist, though she didn’t tell Harry she had cut the man loose to float in his own sea of insecurities without her. During their marriage she had been direct but Harry had lost the privilege of her blatant honesty. Did that mean she wasn’t really his friend now? Direct would have been: it is none of your business, Harry.

Over appetizers (barbequed oysters) Harry asked about Jane and again with soup (curried pumpkin) and then at the main course (salmon in parchment), he brought the conversation, which had been mainly about his new girlfriend --an anthropology graduate student -- back to Jane. Why had he never met her?

Inevitable as it was that they would eventually cross paths, Oatmeal was uneasy. She was not at all worried that Jane would be attracted to Harry--that just could not be -- and the slight worry that creased her brow when she assumed Harry would be bowled over by the younger woman was more concern for him, mixed with self-criticism that Harry was no longer her problem, or at least did not have to be, and then more than a slight annoyance that Harry almost acted as if he were still married to her, though with his bedroom conveniently across town. Some bungee cord still connected them: she on the bridge holding the end of the cord while Harry bonged up and down below. This image was quickly followed by another, surprising one: she let go of the bungee and smiled as Harry spun endlessly into a dark abyss.

“You’ll call me when Jane is back in town, won’t you?” Harry sipped a dessert wine he had brought with him to drink along with Oatmeal’s baklava. Then he left, pecking her on the cheek. No sooner had the door closed than Jane came in the back door and helped herself to a piece of the sweet dessert.

“Harry?” she said.

Oatmeal nodded. She thought, I can catch him. And maybe he shouldn’t drive with dessert wine raising his blood alcohol. I can run out and wave him down and invite him in to meet Jane. But she did not.

The next morning Jane joined Oatmeal at the pine kitchen table and poured herself a cup of coffee, black. Oatmeal was eating leftover baklava, her coffee mixed with milk made out of peas.

“I feel like crap,” Oatmeal said, making her point by sneezing three times into a paper towel. Jane got up and returned a few minutes later with an orange, yellow and white box of Oscillococcinum, a homeopathic flu remedy.

“Take this.”

Oatmeal smiled with skepticism but nonetheless opened a vial and popped the sweet round white pellets under her tongue, thinking as she did so that this feverish feeling could be a gift from Harry, better still, his Argentinian anthropologist.

“This won’t do anything,” Oatmeal said.

“Consider it an effective placebo.”

“I read about swine flu this morning. Someone calculates the human population has to go from almost eight billion to five hundred million in order to be sustainable. This person hints that the designers of the New World Order have created swine flu as a genocidal tool.”

Jane rolled her eyes.

“You don’t have swine flu.”

Later that day, Oatmeal had no signs of cold or flu. Remedy? Placebo? Dynamite immune system? She ate an orange and made herself a pot of green tea, to celebrate a feeling of vibrant health.

Jane left without saying goodbye.

Three weeks later Oatmeal wandered in to the kitchen, wearing striped pajamas and a vintage chenille robe, to find Jane with a pot of newly brewed coffee, glasses of fresh orange juice and a tray with toasted bagels, lox, cream cheese, sliced red onion and capers. They carried the breakfast to the porch and ate in silence.

Oatmeal began to tell Jane what was on her mind, how happy she was to be living by herself, how much she enjoyed being able to get up when she wanted and do whatever she wanted without Harry’s presence, how day by day, she was leaving the house less frequently, sometimes shopping for a few days and then not going out until the food ran out, sometimes letting messages pile up on the answering machine, answering emails sporadically. When she had finished, there was a silence. She added, “And sometimes it’s too quiet. I put the radio or tv on for company. Netflix. Old movies.”

Jane was knitting a long strip with soft yarns in the vibrant Southwestern colors of her house, or rather Oatmeal’s house now.

“You need a dog,” she said.

Oatmeal spent the day on the Internet researching dogs. At first she thought it might be fun to have a big dog, even a very big dog like a Bernese Mountain dog or a Saint Bernard. But after all, she wasn’t looking for something the size of a husband. She read about border collies and Dalmatians, little Havanese dogs, cavalier dogs named after King Charles, water spaniels and Tibetan Terriers raised to be meditation companions for monks. Each breed she wanted in turn. That night watching television with Jane she saw a designer dog food ad featuring a woman asleep with a white West Highland Terrier looking sweet and vigilant at her shoulder. The caption said, “I promise to be here when you wake.”

”I want a dog like that,” Oatmeal said. “Small, fluffy, loyal, affectionate. A dog for an older woman. But breeds are so expensive.” Then, pensively, “Maybe I really want a mutt.”

The next morning Jane told Oatmeal they were going to pick up her dog. After a two hour drive in a downpour they arrived at a house painted dark green where they were greeted by a woman who introduced herself as Crystal. In her kitchen five puppies were rolling over each other. The room smelled sweetly of puppy pee. Oatmeal dropped to the floor and fondled each puppy in turn.

Crystal told her story. She was a breeder of champion (she lifted her chin) West Highland Terriers. She hired a dog walker for her precious charges. And so when a female, her favorite, swelled with an unplanned pregnancy, it was clear that something unacceptable had happened on one of the walks. The dog walker was fired on the spot, of course (she sniffed), so these six puppies of unknown lineage were to be disposed of quickly, and for free. Crystal’s attitude was that of a dowager grandmother seeking quick adoption for the illicit child of a wayward child who had sex with a mysterious and unidentified stranger of unknown pedigree.

While the auditioning puppies scrambled for her attention, Oatmeal liked the idea of not knowing what her dog would grow up to be.

“Wait! One’s missing,” said Crystal.

She opened the door and there was the sixth puppy, asking to come in. She had somehow gotten outside and had covered half her little white body with mud. Oatmeal was still sitting on the floor. The puppy wobbled over to her on unsure puppy legs and climbed into her lap.

“Meet your dog,” said Jane.

The puppy took over much of the empty space in Oatmeal’s life. She bought a book on dog training informing her that puppies must be kept in a crate. “Always take your puppy from the crate immediately to the yard. When your puppy pees and poops, reward her lavishly and put her back, empty, in the crate. That way you will never have an accident in your house.” Oatmeal bought a crate and when she went to bed, she put the puppy in it, but she howled like a soprano, a sound Oatmeal ignored for about ten minutes --“You sound like Mimi in La Boheme”-- then took her into her bed. “Maybe I should call you Puccini, my little opera dog.” The puppy snuggled by her neck and licked her cheek. In the morning, they went immediately to the yard where Puccini was rewarded lavishly by name for good behavior. And that was the end of the crate.

“That’s a dog!” Harry said, when Oatmeal opened the door for him on Tuesday night. “What’s a dog doing here?” He handed her a bouquet of irises and dropped his leather briefcase by the door. “Oats, you can’t have a dog. How will you ever travel now? I know you, you won’t put a dog in a kennel. Dogs are messy. They chew things. They bite. Look at your arms!” Indeed, Oatmeal’s arms were covered with bandaids from razor-sharp baby teeth.

Her name is Puccini.” Harry scowled.

Over dinner (lasagna made with ground lamb), Harry, the Cat person, continued to rail against the dog, referring to her only as “it”. Oatmeal, becoming increasingly annoyed, let him go on without comment. Puccini, who was rewarded with a screech when he tried to make friends with Harry by pulling on his pant leg, trotted off to chew on the handle of the briefcase by the door as if it were a huge rawhide bone. When he noticed, Harry leaped from his chair and might have hit the dog if Oatmeal had not be fast enough to get between them. She disengaged the teeth, said “no, no, bad dog,” (way too casually for Harry) and took the briefcase to the table to inspect the damage in the light. There were a few teeth marks on the handle, nothing she would have bothered with had it been hers, but knowing Harry would seethe every time he looked at the briefcase, which was really worn out anyway but could never be replaced -- it was a gift from his father -- she offered to have the handle replaced.

As a married couple, they had often each put their papers in this briefcase when going somewhere together and so Oatmeal did not feel intrusive opening it to empty the contents into a bag from the hall closet so that she could take the empty briefcase to repair the minimally damaged handle. But as the clasps snapped and the top opened under the strong hall light, Oatmeal found herself staring into the provocative eyes of Harry’s Argentinian girlfriend. His almost completely nude anthropologist girlfriend.

Oatmeal felt restless and agitated after the disastrous lasagna evening, which ended with Harry, his face vermillion, snapping the injured briefcase shut, racing for the door, and tripping over Puccini who howled with operatic splendor. Oatmeal revisited the moment they decided to separate. She had never thought of leaving Harry before the instant when the word “Enough” was said humorously in tandem. But was it really so in synch? Could Harry have said it a fragile second earlier and she (unconsciously) picked up on it? Had she read his mind? No, not that. “Enough” was a word they often used as a shared private joke after reading Updike together. So it was not so surprising that they said it simultaneously. Or was it? Had Harry been eager to be free before that moment? Had he, and this thought was accompanied by a real shock, been involved with the Naked Scientist (whose name she did not know) before that moment? Had he called this Enigma right away and said, “Good news: something has happened. Divorce is not going to be a problem.”?

The next time Oatmeal and Jane met for tea, Oatmeal was still flustered about Harry. She didn’t know if she should expect him for dinner Tuesday or if she should email him, or even call him. What if she made some elaborate dinner, he didn’t show up, and she was left with a soggy plate of leftovers for breakfast? He hadn’t emailed after that awful night. He still had the gnawed briefcase which she agonized over repairing.

Jane listened, with Puccini asleep in her lap, totally relaxed with her four paws pointed to the sky and her head hanging toward the floor.

Oatmeal wound down.

Jane said: “Harry is your past. Move on.”

What Jane said was right, of course and hearing the words gave Oatmeal permission to stop debating over what to do. Let Harry contact her if he wished. She felt in retrospect that her crimes-- owning a dog who made insignificant (repairable) marks on Harry’s precious briefcase handle, perhaps even going over a boundary in opening the case-- were miniscule next to the affront of Harry’s having brought his naked girlfriend into her house. She was embarrassed for the woman as much as for Harry, since Mlle X would probably not have expected that picture, given to Harry under who-knows-what circumstances, to have landed under the surprised eyes of the ex-wife, who found herself annoyed rather than jealous. At least Harry had not opened his briefcase in front of one of his math classes, there was that.

Oatmeal woke up to a feeling that preceded its definition, a sense of something missing that gradually took shape as Harry. He was no longer squabbling with her, scrambling around in her thoughts as he had since the dismal dinner. In his place was a delicious feeling she tried to hold in her drowsiness but that all too soon slipped into an image, a memory of being in the Art and Music building at her university, in a room smelling of oil paint and turpentine. A fragrant spring breeze came though the open window of the ivy-covered brick building. Somewhere downstairs someone was playing Chopin. Oatmeal saw herself as a student, staying after class to complete a charcoal drawing of a live model.

How long had it been since she had felt such joy and excitement, unmarred by anything?

Later that morning Oatmeal drove to the art supply store and lost herself in the aisles of brushes and canvases, thick pads of watercolor paper, tubes of oil paint and water colors, pastels, colored pencils. Several hours later she wheeled a cart to the checkout, leaving with several bags of new, unopened, beautiful materials. Signing the credit card slip with a flourish, she joked with the cashier that she was opening her own art supply store. So what? Harry probably spent more on a single vacation with one of his girlfriends.

Oatmeal played some Chopin and cleaned out her office room, putting all files and books out of sight so when her computer was asleep, there was not a word in view and nothing on the walls. On her empty desktop, she put a piece of water color paper, a glass jar of water, a small palette, her water colors, and her new brushes. The blank sheet of paper: to writers that was supposed to be terrifying but Oatmeal felt only elation. She was about to discover something about her artistic style, as a writer would discover voice. A small circle of cobalt blue dripped from the end of her thinnest brush and melted onto the rough surface of the paper. And then another. Gradually a bright blue fish with green stripes took shape on the paper. And then another and more fish until the page was swimming with brilliant tropical fish from her imagination. She printed colored pictures of fish from the Internet and copied some of them, but the fish that just appeared on her paper were better. Big fish, little fish, fish of different sizes on one page; pastel fish, bright fish; fish in water color, pastel, oil; fish in water and fish on white backgrounds; lone fish and fish in schools. She forgot to eat, stayed up late into the night, dreamed of fish.

The walls of her office, now her studio, were covered with fish pictures, tacked up with push pins. It began to feel like being in an aquarium, swimming through air with her wall fish looking down on her, up at her, straight at her. She remembered sitting in an exhibit of Monet waterlilies exhibited in a circle.

On Wednesday morning she woke to realize she had forgotten to wonder if Harry was going to show up for Tuesday night dinner. He had not; good thing since she would have had no dinner for him. She was very hungry. After making pancakes, she went into the fish room and tacked up pictures left to dry overnight. As the last pushpin was sinking into the wall, she noticed Jane in the doorway.

“Like my fish?”

Jane nodded; Oatmeal beamed.

“Now buy yourself a good camera.” And she was gone.

Oatmeal researched online, reading comparisons, looking at specs and sizes. She explained to the man who owned the local camera store that she had photographed years ago using film and so was new to digital. Not being able to make up her mind, she settled for upgrading her iPhone.

Her next meeting with Harry was a chance encounter while walking Puccini on a public path by the river. Growing up, Puccini had the lovely gentle face of a Westie but her legs were longer and she had brown spots. “You’re a Westie on stilts,” she explained to her puppy. Her training was coming well, but she went nuts when she found a new dog or person to play with, leaping and straining on the leash. Oatmeal saw Harry at a distance and wondered if she had time to turn and run but in that instant Harry saw her, too. The look of terror on his face made her bold. She took a deep breath and continued. Harry held the unfortunate briefcase at his right side; his left arm was around the shoulders of a young woman who looked like but was not the woman in the picture.

When they were about ten feet away, chaos broke out. Puccini leaped forward wagging her tail madly just as the young woman disengaged from Harry and collapsed to the ground in a balanced squat catching the white dog in her arms. Squealing with delight, she rubbed the puppy from top to bottom while Puccini removed all the makeup from her face with her happy tongue.

Oatmeal met Harry’s startled eyes,

“I guess your friend likes dogs,” she said.

He smiled warily.

“This is Ariadne,” he said. Ariadne, of course.

Ariadne disengaged enough to reach forward and shake Oatmeal’s hand.

“My ex-wife,” Harry explained. Is he ashamed, she wondered, of having an ex-wife named Oatmeal or was ex-wife adequately explanatory of her place in the world?

Oatmeal did not feel jealous of Ariadne’s relationship with Harry, or of her youth as such, but she did envy the way the young woman’s hips and knees supported her decline and restatement to a vertical position so gracefully, without a single complaint. That was something Oatmeal wished she could do.

Puccini looked up at Oatmeal. Oatmeal looked at Harry. Harry looked at Oatmeal. Adriadne looked from one to the other and then settled on staring at the puppy.